|

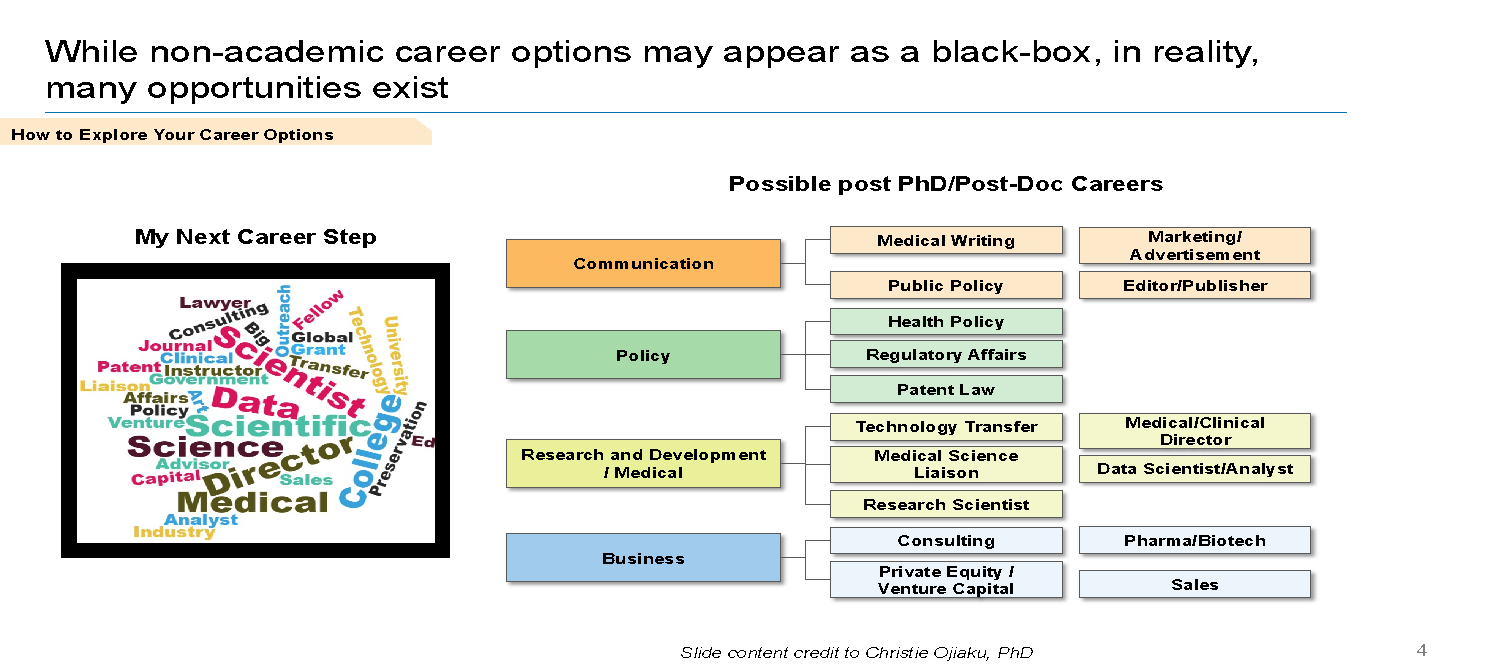

Words by: Dr. Sindhuja Devanapally Edited by: Dr. Lucie Yammine, Dr. Laurie Herviou, Dr. Conchi Izquierdo  Recently, INet-NYC hosted an informative and timely career development seminar series led by professional development coach, Dr. Valentina Schneeberger. By day, Valentina is an Associate Director of Market Research at Sanofi, but her other passion lies in coaching PhD-holders for career success. After a PhD in cancer biology at University of South Florida and a postdoctoral research career in Memorial Sloan Kettering, New York, Valentina transitioned out of academics into the world of life-sciences consulting at Charles River Associates. She sets an example for how scientists with expertise in biology can still contribute to career sectors most academics are unfamiliar with. In this four-part webinar series, Valentina exemplified the plethora of opportunities there are for anyone with a PhD degree, outside of academia. As part of the series, I summarize a list of actionable steps that Valentina provided for career exploration and successfully landing a job. Part 1: How to plan for your post-PhD career There are many opportunities that exist for postdocs outside of an academic career. Slide from Valentina Schneeberger’s talk. Content credit: Christie Ojiaku, PhD. While the academic work environment is the most familiar for many of us, many individuals realize along the way that perhaps other professional directions are better to explore. However, the problem arises when one does not know where to begin. Through sequential steps broadly divided into three phases, Valentina used this seminar to provide the attendees with a guide to getting started on the career exploration path: i) Identify interests and priorities through self-assessment: Valentina suggests self-introspection and reflection on personal priorities in addition to examining your professional interests. Combining these aspects can help you develop a list of must-haves you can focus on during a career search. You can prioritize in order of importance these factors: intellectual stimulation, income level, work culture, flexibility in work hours, location of the job and amount of social interaction and travel. There are several self-assessment resources that exist, such as the Yale self-assessment worksheet and the more popular myIDP by Science Careers. These resources help you expand your thoughts to imagine a career you previously never considered. Valentina emphasized that one must not set their limited expectations of oneself to inhibit exploring with an open mind when it comes to career exploration. ii) Research the career options that align with your interests and priorities: As a PhD-holder, there are many ways we can delve deeper into finding roles that match our interests. All of them somehow relate to professional networking. Some examples include:

iii) Design an approach to explore the career option of your interest: If you are in the first step of transitioning out of academia, job preparation can be an almost full time job. Yet, it is a necessary step to successfully make the career switch. In this phase, Valentina strongly suggests committing a time chunk dedicated to job searching. This means that clear boundaries are set and expectations are met while balancing it with your day job. A schedule of tasks needs to be drafted to check off the list as part of necessary job skills preparation or for the job interview. Finally, you need to simply execute this list of tasks and keep yourself accountable as you track your progress towards the new job applications. As you may notice, career exploration demands a good amount of time and energy from you but for a favorable outcome, you would need to have a clear channel of communication with your PI. This begins with setting your expectations with your PI on the progression of your publication and your timeline of exit from the lab. At the same time, Valentina suggests communicating your future needs about aiming for a different career path while balancing current expectations from your PI and delivering results within your current role as a postdoc. How to network for success

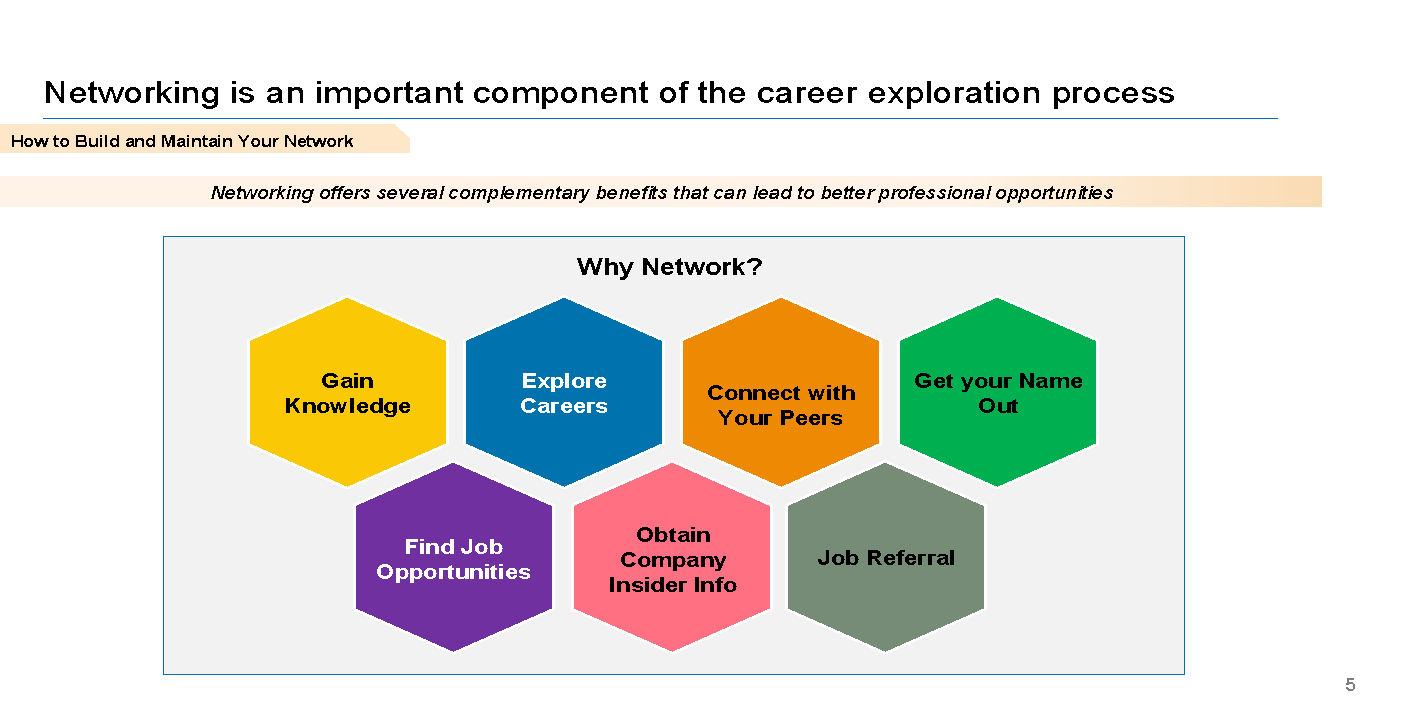

In this webinar, Valentina showed the importance of networking towards building chances for a career opportunity. She advised that successful networking significantly improves your ability to be hired and provides a series of steps to effectively network.

0 Comments

Words by: Lucie Yammine Edited by: Marta Collu and Laurie Herviou To celebrate Earth Day during the month of April, INet-NYC has decided to partner up with My Green Lab® to raise awareness about energy consumption in our labs and to work together towards a more sustainable approach of science. My Green Lab® is a US based non profit organization that works with labs all over the world. Their goal is to bring awareness to the environmental impact of laboratory operations and share best practices to make changes that lead to science sustainability. Together with our guest speaker Christina Greever, Sustainability Program Manager at My Green Lab®, Dr Marta Collu and myself hosted a webinar about laboratory sustainability and Green Labs movements you can watch or rewatch on our YouTube channel. Reducing the environmental impact of research has not only interested researchers in the NYC area or the US, but also around the globe. We were very pleased to count among our attendees, scientists from Australia, Canada, Colombia, India and the UK! When we think about waste in a lab environment we tend to only think about single use plastic consumables and packaging, and forget about the energy consumption and the amount of water used in our lab processes. Therefore, Christina walked us through the impact of our research, using very specific and striking examples. Did you know that one Ultra Low Temperature (ULT) Freezer consumes as much energy as one average US household per year? And chilling it up to -70°C instead of -80°C can save as much as 30% of the consumed energy. *Laboratories discard 2% of the global plastic consumption* According to Christina, Science is one of the final frontier of sustainability, because every lab is as complex as the research that is conducted. But sustainability can be reached in scientific processes in a lot of different ways. We do know that science is very resource intensive, then how can we combat this excess resource use? There are more and more institutions-based green lab programs growing around the world. There is interest and leadership towards sustainability coming not only from universities but also from industry and companies that are committing to greening their manufacturing processes. “You are not alone in caring about reducing the environmental impact of science” A few easy steps to get started:

We can also reduce waste with green chemistry, and your lab doesn’t have to be a chemistry lab to follow the 12 principles of green chemistry! Beyond Benign is an organization that focuses on these lab practices. “Green chemistry is the design of chemical products and processes that reduce and/or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances. This approach requires an open and interdisciplinary view of material and product design, applying the principle that it is better to consider waste and hazard prevention options during the design and development phase, rather than disposing, treating and handling waste and hazardous chemicals after a process or material has been developed.” When we are at home, turning off lights after leaving a room or running dishwashers when they are full seem like a non-brainer. The simplest actions can have a big impact on the environmental cost of a lab in terms of energy consumption, because they have a much bigger impact in our labs than we can imagine. “If every lab turned off one piece of equipment over night, it could save the equivalent of taking over 10,000 cars off the road.” Among the best practices Christina listed, she also gave the examples of shutting the chemical hood sash to save two average US households worth of energy, defrosting and removing ice for our cold storage for them to operate at maximum efficiency. To support scientists in their quest towards best practices, Christina said that My Green Lab has launched different programs designed so that individuals, laboratories, institutions, suppliers can interact and engage together to transform how science is done around the world. Here are a few of them:

Using this label, as scientists and purchasers, we can standardly compare and choose the most sustainable and eco-friendly products.

In summary, the smallest changes in our daily work life can have a massive impact on our environmental cost. “You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

-Jane Goodall- Words by: Dr Rebecca Caeser Edited by: Dr Lucie Yammine, Dr Vacha Patel and Dr Rinki Saha Women in science have long gone underappreciated. INet-NYC did our part to redress this by hosting a Women in Science month. We featured a female scientist’s story and thoughts on our blog and social media (twitter and instagram) every day for the month of March. We hope many of you walked away from it feeling inspired, relieved that things are changing already, yet still driven for more change. Here are three themes that stuck with us: Motivation One of the themes that ran through all of our interviews was our interviewees love of science. Dr Bhama Ramkhelawon (NYU Langone) spoke for many when she said that her motivation comes from performing “an experiment to address a question - and it works. Feels fantastic. Feels like the first bite of ice cream on a hot summer day”. Many also mentioned that their motivation is driven by a sense of doing something meaningful which is often fuelled by speaking to patients and/or their families. But several argued that doing great science is not enough to progress equality. Dr Linda Molla (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) believes that we need to shift our thinking about how leaders within science are rewarded. Currently, individual successes are recorded, but we need to put more focus on “how they manage and help employees or trainees to develop to achieve their goals”. These efforts will be vital to achieving greater gender equity, and are often currently unrecognised. As Dr Molla says, addressing “ineffective management practices would overall create healthier academic lab environments and help retain women in science.” Several interviewees advised focusing on your productivity, rather than how many hours you put into a project. Dr Federica Valsecchi argued that "Being “workaholic” does not always mean being productive." A similar sentiment was shared by Dr Sandra Franco Iborra (New York Genome Center) who said that “one of the most dangerous rules is that you can’t have a work-life balance if you want to be a successful scientist”. We ought to let go of feeling guilty when not working 24/7. And Dr Itziar Irurzun Arana (AstraZeneca) had some good advice for staying motivated through adversity: “don’t be afraid of making the wrong choice, making mistakes is part of the path”. Family It’s no secret that women often feel a pressure to choose between starting a family and progressing their career. Dr Gayathri Srinivasan (Emory University) feels that “the roadblocks for women are that the biological clock and the tenure clock or climbing the corporate ladder are exactly at the same time. This makes for hard choices.” Yet, women should not feel like it’s either all science or nothing. Dr Elisa Venturini (Natera) gave some food for thought on this topic: “Mentors and colleagues who value our expertise will not make us choose. Finding that environment will not be easy, but we should not give up our dreams of starting a family, but rather we should focus on finding that workplace where we are valued even more because we have a family”. Our interviewees had some good tips on how to achieve a healthy work-life balance. In prioritising her work, Dr Lilian Lamech (Chemeleon) said “I often re-evaluate based on the needs of the coming weeks and make sure the goals are manageable. It’s also okay to say no." And as Dr Thu Huynh (Midwestern University) told us, “work-life balance means setting boundaries.” But they also argued for deeper structural changes, such as implementing better paternity and maternity leave, allowing for flexible work hours and affordable daycare for all. As Dr Hannah Meyer (Cold Spring Harbor) argues, women can’t fix equality on their own: “the burden of trying to make a change is often placed on the minority group, here women – this takes away from time that can be spent on research.” Visibility

One of the key obstacles to equality in science identified by our interviewees was visibility. Dr Karuna Ganesh (MSK) points out that “girls are steered away from STEM early on.” This lack of role models is damaging and leads to a shortage of women higher up the scientific career ladder. But role models don’t necessarily have to be celebrity scientists. As Dr Linda Molla (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) said “If we want to impact change, each and every one of us needs to speak up in our workplaces”. Dr Gayathri Srinivasan (Emory University) agrees: “we will all have to come together as a society to improve women’s visibility in science”. Many suggested that we need equal representation and provide opportunities for junior/early career scientists. But to achieve this, there was a general consensus: we need male allies! Dr Alicia Perez Porro (CREAF) argues that “we need men to step down from manels, from all-men selection committees etc, and to fight with us for equal salaries, equal career opportunities, to take an active role for diversity and inclusion in STEM”. Lastly, a general advice that many would have given themselves if they were starting their career today was to look for mentors early on in their career! As Dr Triparna Sen (MSK) argued “The right mentor will guide you to seize opportunities, open doors for you, will be a sounding board as you make difficult career choices and will champion for you”. To dive deeper into all our female scientist life stories and thoughts on this topic, check out full interviews on our blog and also youtube channel! Words by Dr. Marta Collu Edited by Dr. Laurie Herviou, Dr. Conchi Izquierdo and Dr. Lucie Yammine As scientists, we apply project management principles every day, from planning and leading research activities, to effectively engaging and communicating with people. Yet, Project Management is a discipline on its own, and many scientists have chosen to transition from a bench research position to a management role. You are probably a scientist at the stage of exploring alternative career paths, looking for networking opportunities and to know more about what being a scientific project manager actually is. To help you with it, INet-NYC hosted a virtual career development event on February 23rd, 2021, dedicated to Scientific Program and Project Management. Flyer of the event by Matthew Baffuto The event, featuring four experts in the field, aimed to discuss how to sail to a project management career in a relaxed, conversational atmosphere. INet-NYC board members, Dr. Marta Collu, Dr. Rinki Saha and Dr. Zafar Mahmood were the organizers and moderators of this event.

To start, the panelists were invited to give a brief introduction about themselves, describing their background and current role. All trained as scientists and earned a Life Science PhD degree, they transitioned to a project management role, and currently work for institutions spanning academia, private companies, governmental and non-profit organizations. Dr. Linda Molla works as Senior Project Associate at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Stephanie Morris is Program Director at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the National Human Genome Research Institute’s (NHGRI) Extramural Research Program; Dr. Shayla Shorter manages the scientific review of the Lupus Research Alliance research grants; and Dr. Federica Valsecchi is the Immunotherapy Project Manager of the Technology and Development Office (TDO) at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The diversity of the organizations our speakers work for immediately gave us a grasp of how versatile the scientific program and project management fields can be. Next, we discussed what are the most critical skills a scientific project manager should possess. “A big part of this role has to do with knowing the science, building relationships with the people, ‘connecting the dots’ and providing your support and your knowledge to the different scientific teams”.-Dr. Linda Molla As project managers constantly interact with scientists and experts, the scientific mindset surely gives the advantage of understanding the rationale behind the different project phases, and of being able to see the bigger picture. But a project management role also involves much more than science skills. For instance, communication and interpersonal skills are key: project managers engage and communicate on a daily basis with a very diverse audience, from the chief of a company, to the members of a team, or the families of a patient. Therefore, they learn how to distil very complex concepts to a level that is understandable to the targeted audience, as well as how to build strong relationships and trust among people. Dr. Federica Valsecchi added that versatility, organization, and ability to learn are also part of the core skills of a successful project manager. If all the highlighted skills do not sound familiar to you, think about your research. “You take all the skills you acquired throughout your PhD and/or postdoc experience and you just use them in really versatile ways. You all have acquired so many skills in terms of communication, multitasking and troubleshooting, and those can be applied in so many ways”. -Dr. Shayla Sorter Through defining specific aims, creating a research plan, troubleshooting, coordinating with collaborators, and presenting your work you learned how to manage projects! All the panelists highlighted that throughout our graduate school and/or postdoc experiences, we have acquired many more abilities than we think, and it is just a matter of understanding how to translate and put them in practice in a management role. Depending on what your interests are, the growth possibilities and career advancements in the field are blooming. As a great example, Dr. Stephanie Morris is now program director of an NIH division. She also explained that colleagues seeking an alternative path outside NIH, often transition to a research director role at academic institutions. Dr. Federica Valsecchi added that as a project manager of the TDO you often engage with outside entrepreneurs, investors, and industry partners, and you may become interested in transitioning into business development. Many more interesting points were touched upon during the event, and you can watch the full discussion here. By sharing their experience and advice, our panelists showed us how this job represents a fulfilling career choice for STEM PhDs who are interested in pursuing a non academic career and still love to be engaged with science. During a conversation with Dr. Linda Molla a few months ago I was captivated by her depiction of the role of a project manager: the one on the backstage rather than on the frontline, leading people, giving support and making things happen. If this is what drives you, start exploring this path! Words by Rinki Saha Edited by Conchi Izquierdo, Lucie Yammine and Laurie Herviou There have been many events in the past which encouraged society to reflect on the expectations of diversity and inclusion, but 2020 has been the year, while amidst an ongoing pandemic, the whole world came together to act towards some real change. In light of those memorable historic moments, INet-NYC organized a panel discussion on Tuesday, January 12th, 2021, called “Diversity and Inclusion in Academia: Perspectives from Europe to the US”. Flyer of the event by Matthew Baffuto INet-NYC presidents, Dr. Conchi Izquierdo and Dr. Laurie Herviou, were the two amazing moderators for this event. Our guests for this discussion were Dr. Lidia Borrell-Damián from Science Europe and Dr. Yaihara Fortis Santiago from MSKCC. Both panelists are very passionate and have wealth of knowledge on this topic of diversity and inclusion. They showed us interesting data that helped us understand how much work still needs to be done to create a more diverse and inclusive environment. If you are interested, here is the video link for the whole event (also at the end of the article). To start the discussion, Dr. Fortis explained that diversity in academia mostly covers all the aspects of gender, sexual preferences/identity, religion, ethnicity, races, disabilities or abilities, etc. Dr. Borrell added that in Europe, it is only allowed to record data on gender while racial discrimination data are not available. In the US and Europe, the religious belief data is not publicly available. Interestingly, diversity data shows that different ethnicities need support in a different aspect. For example, in the US, from undergraduate to faculty level, Black and Latinos are not necessarily suffering from the same problem in academia. It is not a monolith. The most affected group is Native Americans: their representation is so alarmingly low that they are not even included in diversity data. Dr. Fortis highly encouraged everyone to look at the ethnicity representation data regarding their field on the National Science Foundation website. Dr. Borrell also showed us some interesting data, which indicated that the representation of women in academia is approximately 48% but 20% fewer women transition from researcher to principal investigator positions compared to men in the field of life sciences. She also pointed out that, as the data on ethnicity is not available in Europe, it is necessary to voice this problematic situation even more. The inclusion aspect in academia is less discussed compared to diversity. Dr. Fortis explained that the basic concept of inclusion is much harder to measure, and thus to change under any given circumstances. A more inclusive environment indeed needs cultural changes, which takes a longer time. "Inclusion is this notion that everyone, regardless of any of the social identifiers, have the right to be respected, appreciated and valued in the spaces that they occupy." Dr. Fortis Next, we discussed the importance of diversity and inclusion in academia. Dr. Borrell stated that diversity and inclusion are one of the key ingredients to make a better society for the next generation. She provided a whiplash study as an example to pinpoint the importance of diversity to improve research accuracy and quality. This study argues that, when engineering models simulating and analyzing whiplash scale-down data acquired on a male population to draw conclusions on a female population, it is not scientifically accurate. There are thus scientific and societal reasons behind the importance of diversity in scientific research. There is no doubt that, if scientific studies would have continued only in one gender, finding a cure for the whole population would be impossible. Dr. Fortis brought up another perspective on the question, with an amazing example of Dr. Esteban Gonzalez Burchard physician-scientist at UCSF and how he came up with a solution to the prevalence of asthma death in the Hispanic/Latino population in the northeast US. This incident and many other examples indicate that different people aim to solve the same problem with a different approach, which is essential for the accelerated advancement of science. In short, a more diverse environment is likely to make more progress in the scientific world in a shorter period of time. What are the difficulties of diversity and inclusion in academia? From her experience, Dr. Fortis stated that one of the biggest challenges of doing diversity and inclusion work is that it is invisible and diversity works are not compensated nor valued. Most of the time we are in a rush and want a manual or checklists to make a workplace more diverse and inclusive. There is not a single solution available that can change everything over-night. Dr. Fortis mentioned that social scientists have done some magnificent work that can be used to build a strategy to make a workplace more diverse and inclusive. The strategies of creating a diverse environment need active collaboration between social scientists, anthropologists, and organizational psychologists to use their collective knowledge for recruitment procedures. Dr. Borrell portrayed a completely different angle on this topic. She explained the importance of research assessment in the career of an academician. She also showed interesting data on how different aspects such as gender, discipline, affiliation, seniority, ethnicity, and disability are taken into consideration when juries are evaluating the career of the candidates. She highly recommends that European research assessment panelists get the proper training to avoid personal biases. "The sustainable solution is education, teaching about the importance of equality and inclusion from a very early age." Regarding the necessary actions towards a more diverse and inclusive environment in academia, Dr. Fortis suggested to start scrutinizing the available strategies of the recruitment committees, be it graduate or faculty level. There are always lots of biases that exist during the admission procedure, it is not straightforward or empiric. For instance, meritocracy or from which institution the candidates were previously trained highly impact the recruitment decisions. A strategic direction should be employed to avoid these already existing biases. At the individual level, we all need to unlearn and acknowledge our personal biases and take action to be part of a more diverse and inclusive environment. Dr. Fortis reminded everyone that minority groups should not be the only ones raising their voices to influence changes: it is everyone’s duty. Dr. Borrell also advocated that institutional leadership and their public statements regarding equality or inclusion policies are of great importance to influence changes. "We all have to want to do better and be intentional in order for us to move forward as a community." Dr. Fortis "We all have to take our part of responsibility to make a better society that is more inclusive and more respectful." Dr. Borrell We tried to touch upon all the basic points which were discussed during the event. Our panelists from two different continents inspired us that everything is not about problems: we have a ray of hope because a lot of people are talking about this issue and many dedicated scientists are working very hard towards making a more diverse and inclusive future.

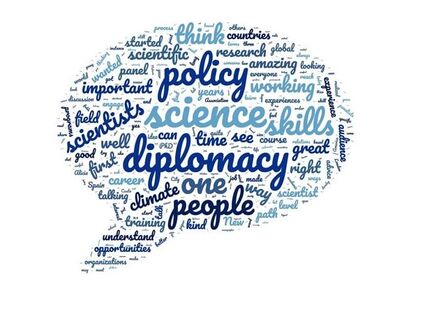

To go further and become more aware (more resources mentioned during the discussion): Words by Ipshita Zutshi Edited by Laurie Herviou & Conchi Izquierdo Climate change, deadly pandemics and diseases - the argument is often made that the world now, more than ever, is in dire need of scientifically-driven policy making strategies. While true, we would argue that the world has always needed science diplomacy, and moreover, there have always been highly talented professionals navigating these uncharted waters of what we now call science diplomacy. With an increasing push to standardize this profession to make it a more linear path, INet NYC organized a career development panel discussion on Monday, May 18th, 2020, called “Science Diplomacy: how one can foster the other?”. The event was spearheaded by INet NYC board member Laurie Herviou, a postdoctoral researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and brilliantly moderated by Alessandro Allegra. The invited panelists included Dr Alicia Pérez-Porro, Dr Lorenzo Melchor, Dr Melania Guerra, Dr Jean-Christophe Mauduit, Dr Marga Gual Soler, and Dr Jessica Tome Garcia (Detailed bios for each of the panelists are provided at the bottom of this article). The outcome of their efforts is a goldmine of information for opportunities to transition to a career in science diplomacy. We hope that you can walk away (or rather, scroll away) having learnt a little more about this truly exciting profession. You can also watch the full video of the discussion here - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ux25ANzPm1c. We used the transcript of the panel discussion to generate a word cloud of the most commonly used terms during the discussion (using www.wordclouds.com). Check out the buzzwords in this field!

So what is science diplomacy? As Alessandro perfectly summarized, “science diplomacy is an umbrella-term that means different things to different people”. He explained that those pursuing science diplomacy often are “hybrid creatures'' of sorts, developing multiple skills and juggling various responsibilities. They hail from various backgrounds, often starting off as scientists, diplomats or social scientists, and perhaps because of this diversity, the very definition of science diplomacy is quite amorphous. Broadly however, all our panelists defined science diplomacy as the interactive medium by which academia, governments, international institutions, private companies, NGOs and regional organizations all connect using science as the common language. As for why the world needs science diplomacy, we highly resonate with the opinion voiced by Jessica, “I don't understand global development without science. I don't understand sustainable development without science. And I don't understand governments without scientists in their parliaments.” What motivated you to pursue science diplomacy? The most consistent drive towards a career in science diplomacy was the general feeling of being “trapped in academia”. For almost all the panelists, there came a turning point in their career, either at the end of their PhDs, or during their post-doc, where they began to question the impact of the work they do - “I felt I was staring into the wall of a cave without being totally aware of how vast the world is”, or “I didn’t want to spend my time in front of a microscope in a dark room alone”, were some phrases heard. Some of the panelists such as Alicia and Melanie described their turning points as “Aha!” moments where certain experiences made everything click for them (Admittedly, their jaw-dropping experiences in Antarctica or in the Bering Strait certainly sounded Aha-worthy). Other panelists such as JC and Lorenzo described this process as a more gradual process of self-discovery, from a course taken, or exposure through volunteering at an organization, that slowly shaped their path. How did you start your career in science diplomacy? Given how diverse and multi-faceted the field of science diplomacy is, it is perhaps unsurprising that the paths taken by our panelists were equally varied. For most of our panelists, fellowships (most of them UN-based fellowships), Royal Societies, workshops and field trips acted as the first steps to transitioning to a career in science diplomacy (For a comprehensive list of these fellowships, scroll down to the ‘useful links and resources section’). Almost all panelists also highlighted the role of mentors in this process, where often finding the right mentor is the first step towards learning how to make this transition. A crucial point raised by Alessandro, JC and Marga, is that this process is not necessarily always linear. It sometimes becomes necessary to take a few steps back, to pursue a masters degree, or an unpaid internship, after already having received a PhD. In fact almost all our panelists went on to complete their master’s degrees in policy after their PhDs, because those programs would give them the necessary visibility and knowledge of the international framework. All the panelists stressed however, that these temporary pauses should not be looked at as setbacks, and that these courses are well worth the extra time. Furthermore, there are now greater efforts to make this career path more linear with more streamlined courses and trajectories available. Given the variety of trajectories one can take to transition, we understand that decision for the ‘right’ path can seem quite overwhelming. Here, we hope that JC’s advice may provide some respite, “It is important to remember that there is no one skill, or one clear educational pathway or trajectory to follow. The field is constantly being defined, and the way to teach knowledge and skills will also continue to be shaped and refined in the coming years.” What skills help for a successful career in science diplomacy? Perhaps the most common advice given by our panelists was to cultivate the ability to communicate. As Melanie rightly said, “If you have the ability of simplifying the science, dealing with the uncertainty around predictions, and maneuvering them into something that can actually lead to action for the policymakers, that is one of the biggest strengths that you can have.” This advice was backed up by Lorenzo who also recommended that one must have, “Entrepreneurship creativity and the ability to multitask because you’ll have to develop quite a lot of projects at once”. Our panelists also recommended developing “soft-skills”. As Jessica mentioned, “It is very important to never underestimate a person and instead try to understand what their culture and passion is and always have an open mind.” Similar opinions were voiced by Marga who told us, “In this field, it is not only important what you know, but also how you say it and whether you respect protocol and know that there’s an order and hierarchy that must be followed.” Resilience was another skill that our panelists repeatedly recommended. As Jessica described, “There are many many skills needed, some of which we have already gained as a scientist because we think and we learn how to be resilient.” This rang soundly with Alicia’s advice - “It is very useful to be able to leave your comfort zone and feel comfortable being uncomfortable”, Alicia also mentioned that her ability to connect things that people don't see the connection between - a scientific paper, an international policy, a local NGO, and to find ways to bring these seemingly different things together has paid off really well in this profession. What if I’m not ready to transition to a career in science diplomacy? We understand that many of our readers care deeply about science diplomacy, and want to look for ways to contribute without completely switching career paths at this moment. We’d like to highlight a key point made by Lorenzo, “You can keep doing research but with a different mindset that your research needs to have some kind of impact at the policy or diplomacy level. To do that you engage in specific meetings, have different international conferences, or different policy gatherings to provide your scientific expertise so that science has an impact in policy and diplomacy.” Several organizations such as the Royal Society, Sense about Science, Campaign for Science and Engineering, and professional societies or networks (Psst...INet-NYC is looking for volunteers) are ideal platforms to engage with science diplomacy as an active researcher. Needless to say, keep engaging with us and our panelists on Twitter, Instagram and Linkedin, and keep the conversation going! We would like to end with the inspiring advice given by Alicia, “when in doubt, just keep swimming”. It may seem like a daunting task but if you stay focused and take things one step at a time, you are sure to achieve success and find a way to navigate these waters. Useful links and resources: Words by Ipshita Zutshi

Edited by Jessica Sharrock Burnout, stress, hopelessness…we in academia are only too familiar with these terms. How many times have we had a paper rejected, had a PI make unreasonable productivity demands, had to deal with the incessant guilt of taking time away from the bench? Mental health issues are pervasive and deeply entrenched across all fields of academia, but sadly often also go ignored. On September 24th, 2019, INet NYC organized an open mic event on mental health that invited anonymous stories from scientists and researchers across the country, which were then narrated to the audience. Several members of the audience also shed their inhibitions and shared their own stories of dealing with the pressures of academia. By narrating stories of various kinds, ranging from annoying co-workers, to frustrating experiments, to serious cases of harassment, our goal was three-fold – first, to provide a healthy environment where one can gain some respite by sharing stories that have probably been festering for a while. Second, to demonstrate to all those suffering from mental health issues out there, that YOU ARE NOT ALONE. Lastly, by narrating a large variety of stories, we hoped to gain a better idea of the breadth and range of mental health issues that plague us in academia. This event was awarded the 2019 Elsevier National Postdoc Appreciation Week Best New Event award and we would like to thank the NPA for recognizing the importance of addressing mental health concerns. The event brought to light several reasons why mental health issues in academia are so widespread. Firstly, in academia, the lines between career and personal life become increasingly blurred. In our quest for success, we discourage time for hobbies, interests, families, and foster a culture of stiff competition where an inability to enjoy spending 12 hours cooped up in front of a microscope reflects too little “passion” for science. Unfortunately, so many of us slip between the cracks because of this culture, where we’re stuck feeling like misfits, or ‘imposters’, or simply not having what it takes. Another recurrent theme across most stories was that academia is a relatively solitary journey. Alone you trudge, dealing with failures on almost a daily basis – failed experiments, grant rejections, rejected papers. Toxic lab environments, competition between lab members, and unreasonable PIs were one of the primary sources of stress amongst our story contributors. Lastly, it became amply clear that most international researchers also have the added stressors of immigration. Most visas preclude international researchers from taking up jobs outside of academia, forcing them to be stuck, miserable, in their current labs, or risk having to go back to their home countries. Bleak as all this it may sound, the event also discussed how the younger generation of researchers are now rejecting the stigmas and toxic expectations of academia. There are several very loud voices championing for better mental health in academia, and it was widely agreed that sharing our stories is a first step to making this career path a more inclusive and welcoming place. Given the current coronavirus crisis, we acknowledge that mental health issues have likely been exacerbated for most of us. The stress of being away from experiments for an unknown period of time, being locked into our shoebox-sized NYC apartments, pressures from PIs to use this time “productively”, job and immigration insecurities, and a constant fear for our loved ones in faraway cities or countries – trust us, we know exactly how you feel! But maybe this is good time to take a break, spend time with a loved one, catch up on healthy eating, take up a new hobby. The experiments will still be waiting for you once this is all over, so for now, just make sure you are taking care of yourself. If you are struggling with mental health issues, please do reach out to counselors, friends and family. If you or someone you know needs immediate help, please contact the toll-free, 24-hour hotline of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Hopefully, with a little bit of help and support, we can work towards making academia a much more welcoming and positive career path than the one we have experienced till now. Words by Vacha Patel

Edited by Ipshita Zutshi INET NYC hosted a formal roundtable discussion and networking reception, “Non-academic career tracks for International scientists” on November 13th, 2018, at the New Science building, NYU. The room had ten round tables, each with an assigned mentor of specific career expertise. The attendees could sign up for three out of nine available topics, allowing them to rotate around tables and meet three different mentors for 20 minutes each. We are indebted to our star mentors who made time from their busy schedule and graced us with their presence, knowledge and shared with our audience their insights. Thomas Clozel at the Entrepreneurship/Data Science table, an international scientist from France, is the CEO and co-founder of Owkin, a company that integrates AI with medical research; also, the first to be backed by Google. Clozel is a Doctor and was an assistant professor in clinical hematology. He enlightened his audience with counsel on the transition from academia, guidance on entrepreneurship and an informal discourse on how to start a company from scratch. Jan Philipp Balthasar Müller at the Data Science table an international scientist from Germany is a physicist by training, with an insightful sense of white-collar independence. By various means like freelancing, he has been self-reliant since his graduation. He’s waiting on his green card through the national waiver program, a topic of great interest in the audience. Vesna Tosic at the Finance/Equity Research/Investor Relations table an international scientist from Serbia, got a Ph.D. from the USA in immunology. Tosic at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, is responsible for the investors' relations while divergently talking to the wall street. Being an international STEM graduate student, she is familiar with the struggles faced by a similar crowd and happily talked about it. Sloka Iyengar at the Science communications table an international scientist from India has done work in research, consulting, science writing and teaching. Iyenger is currently a medical director at Phase Five Communications and she also teaches medical communications at NYU and an online course for educators, ‘Seminars on science’ at the American Museum of Natural History. On being asked by an interested audience how she got the job at the museum, she casually said, “because I know people.” Just again demonstrating the virtues of networking. Matthew Cotter at the Pharma table, an international scientist from the U.K. accomplished his Ph.D. internationally, moved to Canada for a post-doc and then the USA earning two other postdocs. He has been working with Pfizer, a research-based biopharmaceutical company for the past ten years. After spending a fair amount of time as a medical director in oncology, his tenure extended to the position of a senior medical director of global medical affairs. He explored further on the transition to pharma industry and green card opportunities. Upal Basu Roy at the Non-profit table, an international scientist from India is the sui generis from non-profit, has a one-off trajectory with Ph.D., Postdoc at NYU and a master’s in Public health. His work has given him the opportunities to work with a diverse range of people from academia, Pharma industry to the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). Christy Kuo at the Pharma table, an international scientist from Taiwan, with insightful subjectivity on J1 visa affairs and J1 waivers transfiguring to green card opportunities. Kuo has a Ph.D. at Weill Cornell University and later pursued a postdoc at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. She is now a senior scientist at Pfizer. Valentina Schneeberger at the Consulting table is a life science consultant, who explained the elemental brass tacks of consulting. Her academic narrative is a Ph.D. in cancer biology and postdoc at Sloan Kettering cancer center. Schneeberger’s take on this profession is that, “Consulting is a good way to get to another place if you are not quite sure what to do.” She evinces of at least two speakers whose careers were aided by the patronage of consulting. Prakrit Jena at the Entrepreneurship table, an international scientist from India, is a CEO and co-founder of a fast-growing company, LipidSense. Jena’s transition from a postdoc at the Sloan Kettering is a pioneering descriptive essay about a lipid sensor they made. He duly credits his success to the Elab NYC program, funded by New York City for biotech startups. His word to the wise for startups is the importance of board members and/or mentors who are also CEO's of at least two companies. Yukie Takabatake at the Biotech table an international scientist from Japan, has a Ph.D. in cancer biology and postdoc from Mount Sinai. Takabatake is currently a principal scientist at MouSensor, Inc. Being an international scientist and now a green card holder, she hustled into the tangled realm of visa issues bagging a room full of affirmative nods. On the one hand, as different origins, nationalities, and cultures, these mentors have experiences and backgrounds worlds apart. On the other hand, they had worlds in common through their struggles, challenges, in a country and city that’s grim, relentless yet magnificent, vivid, divine. Hence keep watching this space for more events by us, for New York City is full of opportunities and it’s all about being in the right place at the right time. By Chiara Bertipaglia, CUPS

Jaime Jurado, INet NYC Advisory team of ECUSA-NYC On Wednesday May 17th the Columbia University Postdoctoral Society organized an Info Session about Immigration at Columbia University. The event was co-organized by Columbia University Postdoctoral Society (CUPS), INet NYC, ECUSA (Spanish Scientists in USA), Einstein Postdoctoral Association (EPA), Postdoc Executive Committee at ISMMS and co-sponsored by Columbia University Postdoctoral Society (CUPS), Columbia University Office of Postdoctoral Affairs (OPA), Rockefeller University Dean's Office, NYU School of Medicine Postdoctoral Affairs through their BEST grant and Graduate School of Medical Sciences (at Weill Cornell Medicine) Postdoctoral Affair office. The idea was to provide the large community of New York postdocs with information on how to transition from non-immigrant to permanent resident status, or immigrant, in the United States. The event got fully booked within 24 hours. The massive attendance of 185 people from 9 different institutions (Columbia University, Cornell University, NYU, Mount Sinai, Albert Einstein, The Rockefeller University, CUNY, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Rutgers, among others) speaks loud and clear about the discomfort of the time that we are living and the uncertainties that we, the international scientific community, face here in the United States. Research in the U.S. is carried out and progresses thanks to many outstanding international PhD students, Postdocs and associate researchers on non-immigrant visas, who seek to become permanent residents to be able to stay and do the their best Science. According to the National Science Foundation (NSF), the current number of international scientists and engineers in the U.S. workforce is estimated to be 5.2 millions, constituting almost 20% of the sector. This number has increased 2.5 fold in just the last decade. The session started with a presentation about the main categories of visa given by attorney Aviva Meerschwam from Fragomen. Then, a panel of researchers that have successfully applied for and obtained an H-1B visa or a Green Card introduced their case and answered questions collected from the public, discussing the alternatives that students and postdocs have to apply for permanent residency. Panelists included: - Sophie Colombo, from Columbia University, H-1B (academic, professional); - Kiran Kumar Andra, from Cornell University, EB-1A Green Card (obtained with the help of a lawyer); - Hourinaz Behesti, from The Rockfeller University, EB-1B Green Card (obtained without the help of a lawyer); - Chamara Senevirathne, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, EB-2 Green Card (obtained without the help of a lawyer); - Wissam Hamou, from Mount Sinai, EB-2 Green Card (obtained with the help of a lawyer); - Alicia Perez-Porro, from the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, Green Card through marriage (with a pro-bono lawyer); - Jose Ignacio Garzón, from Columbia University, Green Card through lottery. The session was broadcasted live for people who could not attend and the video can be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IR9_-vvWQIQ Let’s summarize the information gathered during the meeting. The status of non-immigrants is for foreign nationals that come to the U.S. temporarily and keep their residence abroad. In the field of academic research, common categories of visas include:

F-1 visa is available to foreign nationals entering the USA for academic studies and are eligible to work 12 months under the Optional Practical Training (OPT), either pre- or post-graduation in the field related to their studies. STEM degrees students may apply for a 24-months extension. J-1 visa allows foreign nationals to participate in an approved exchange program to gain experience, study or do research in their field. Examples of exchange visitors include, but are not limited to, trainees, interns, teachers, professors, research scholars, specialists, students and foreign medical graduates. H-1B visa types are open to professionals that work in a “specialty occupation” and are going to remain in the U.S. for a minimum of 6 years. 65,000 H-1B visas can be issued annually, beginning each year on April 1st. However, certain employers are exempt from this quota (e.g. non-profit and governmental research organizations). Premium processing for this visa type have been temporarily suspended under the current administration. O-1 visas are open to foreign nationals of extraordinary ability in the sciences, education, arts, business or athletics. Applicants have to meet certain requirements such as:

Most of foreign Postdocs enter the U.S. with a J-1 visa, stay for 5 years and then shift to a H-1B type of visa for another 6 years. This can be done as long as they remain in academia. Eventually, as non-immigrants, they may decide to pursue the status of permanent residence while in the U.S. territory. Many do it because they do not want to deal with visa bureaucracy and paperwork every few years. Plus, being a permanent resident is definitely an advantage when transitioning from academia to industry. This change of status from non-immigrant to permanent resident can be done either from an F-1, J-1 or an H-1B visa. The way to become a permanent resident, or immigrant, is by obtaining a Green Card. A maximum of 650,000 Green Cards can be given each year, and they are distributed through the following different application processes:

The employment based Green Card application is a two or three-step process, where the applicant needs to provide:

The employment based Green Card categories are:

The EB-1 category is subdivided into:

The EB-2 category is subdivided into:

The EB-3 category is subdivided into:

For further information on the various Green Card categories, you can also check www.uscis.gov. The audience asked lots of questions to the panelists. We have summarized their answers, at times commented by the attorney. Q1: Can J-1 or F-1 visa holders adjust their status to immigrant? A1: Yes, J-1 and F-1 visa holders can apply for a Green Card while in the United States. Nevertheless, they may have a travel restriction upon filing a petition application to change or adjust status. Moreover, some J visa holders might be subjected to the 2 years rule, which means that they must return to their home country for 2 years after completion of program, before seeking another non-immigrant visa category or permanent residence. Also, since F-1 is not a dual-intent visa category (i.e. it does not permit immigrant intent), there are certain restrictions related to traveling while the application is pending and to the timing for filing the application, which must be carefully considered. As such, it would be advisable to consult with a lawyer before proceeding with a Green Card application while in F-1 status. Q2: Can one apply for J-1 visa when the current visa is F-1? A2: Yes, you can move from a F-1 to a J-1. However, the applicant needs to meet the following requirements:

Q3: What are the requirements for EB-1? A3: There are 10 criteria to demonstrate extraordinary ability in your field. Applicants must meet 3 of these requirements or provide evidence of a one-time achievement (i.e., Pulitzer, Oscar, Olympic Medal).

Q4: How does one meet the scientific standards required to apply for the EB-1? A4: There are no minimal requirements (no minimum number of research or review papers). It is crucial to highlight how your achievements have had a great impact on the American society and internationally. Therefore, more than the number of publications, you may want to highlight how your research has been cited or disseminated. Also, non-scientists will read and evaluate the paperwork, so avoid jargon and technicalities and go straight to the point of why your work matters. Q5: Can O-1 visa be self-sponsored? A5: No, you need an employer or an agent who will act as a sponsor/petitioner. Q6: How many recommendation letters is it advisable to submit? A6: Between 5 and 10 letters of recommendation. It is better if the letters do not come from your past boss or supervisor, but are rather signed by third parties or your future boss. It is crucial to follow the template when writing these letters, which can be crafted also by the lawyers. Hiring lawyers with a science background may help (as it happened to one of the panelists). Sometimes this turns out to be the best option because the right content will be conveyed through the right amount of bureaucratic language. Q7: What happens if the current visa expires while you are in the process of applying for a Green Card or H-1B visas? A7: When you apply for a Green Card or H-1B visas, it is also strongly advisable to apply at the same time for an Employment Authorization (Form I-765) combined with a Travel Document (Form I-131). It allows you to work and travel even if your current visa status expires. Q8: Is it allowed to switch jobs while filing a Green Card or H-1B application? A8: Since this will most likely imply a change in sponsor, it is not advisable to do so. It is definitely advisable to keep the same employer (= sponsor) through the whole application process. Q9: Can one apply for multiple Green Card categories at the same time? A9: It is possible but not advisable. Q10: How much does the whole application process cost? A10: The panelists reported the following experiences: - $13,000, for 1 person + spouse, with the help of a lawyer; - $7,000, for 1 person, with a lawyer; - $1,800, for a spouse of a US citizen, with the help of a pro-bono lawyer; - $2,800, for 1 person, with the application managed by herself, without the help of any lawyer. This included the option of faster processing request (Form I-907) which costs $1,225; - $1,500 for the lottery process. Some lawyers refund you half of the costs if the application is not successful. Q11: How long does it take to get a Green Card, depending on the different categories? A11: It is slower to obtain one of the EB-1 Green Card types than one of the EB-2 or EB-3 types. According to the historical average processing times, the government processing time for the EB-1 visa is about 6 months. Once the EB-1 has been approved, the government takes additional time to issue permanent residence. According to the panelists, the whole application process took up to 18, 9 or 6 months when applying for employment, family or lottery-based categories respectively. The premium service shortens the processing decision down to 15 calendar days. Q12: Can you switch to industry or a different postdoc if you have an academic position-related H-1B? A12: No, you can’t with the same H-1B. If you have an H-1B visa and you want change your employer (which could be a different academic group leader or an industry employer), you also have to change your visa. However, the applicant can apply for a H-1B visa transfer, which allows to start working for the new employer as soon as the H-1B transfer petition is submitted, without having to wait until the transfer is issued. This is the list of the required documents when issuing an H-1B visa transfer:

Q13: Are O-3/O-1 and H-4/H-1B dependents respectively allowed to work? A13: Different from J-2 (J-1 dependents), O-3/H-4 are not eligible. However, H-4 can apply for permission to work only when a permanent residency petition, based on the H-1B’s employment, has been pending for a year or more. Q14: Is it worth it responding to Request for Evidence (RFE) for the EB-1A Green Card or is it better to apply again? A14: RFE is requested from USCIS when a petition is lacking initial documentation or the officer needs additional evidence. The petitioner should respond to the RFE usually in 30 days and will receive a status case respond in 60 days. Keep in mind that USCIS is perfectly able to deny any immigration application without first issuing RFEs, so this might be your last chance to prove what they have asked. Here you will find more information about this process. Q16: How can you apply for Green Card without a lawyer? A16: Panelist Hourinaz Behesti applied for EB-1B without a lawyer and shared her experience. Being EB-1B an employment-based Green Card, the employer (i.e., the University) was the “Petitioner”. The applicant was the “Beneficiary”. Applicants need to have a title other than “postdoctoral fellow/associate” as the USCIS does not recognize “Postdoc” as a permanent position. However, a transition to “Research Associate”, for example after the postdoc position, is considered a permanent position. The employer has to write the cover letter based on material provided by the applicant and has to fill out the forms. On the USCIS webpage, all relevant forms can be downloaded in the “forms” tab. Here is the EB-1B forms checklist:

Q17: As a scientist/researcher, would it make sense to apply for EB-1, EB-2 or EB-3 types of Green Card? A17: EB-3 is for professionals, skilled workers and other workers, which could certainly include scientists/researchers. However, since scientists/researchers usually have advanced degrees and good credentials, it would be more appropriate for them to apply for EB-1 or EB-2 rather than an EB-3. Q18: Who is eligible to obtain a Green Card through family? A18: The following categories are eligible:

|

Archives

May 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed